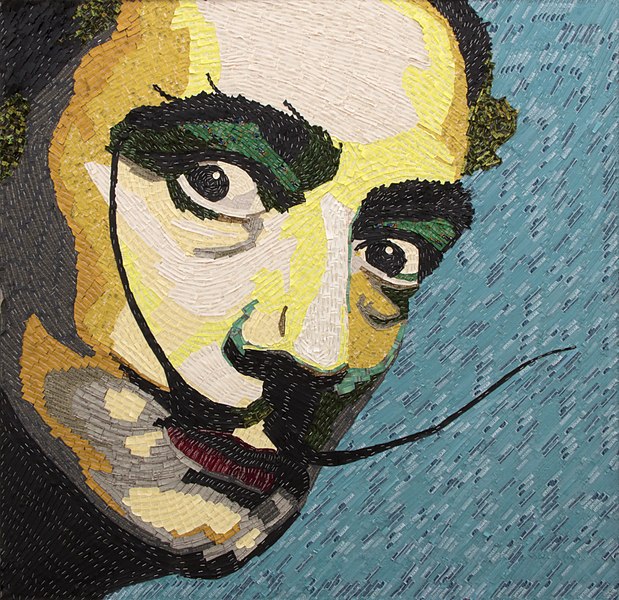

A surrealist’s dream

Salvador Dali painted Christ above his own Catalan coast. The Jesus story is endlessly adaptable to the contours of our life, so that in the end we see our own face reflected.

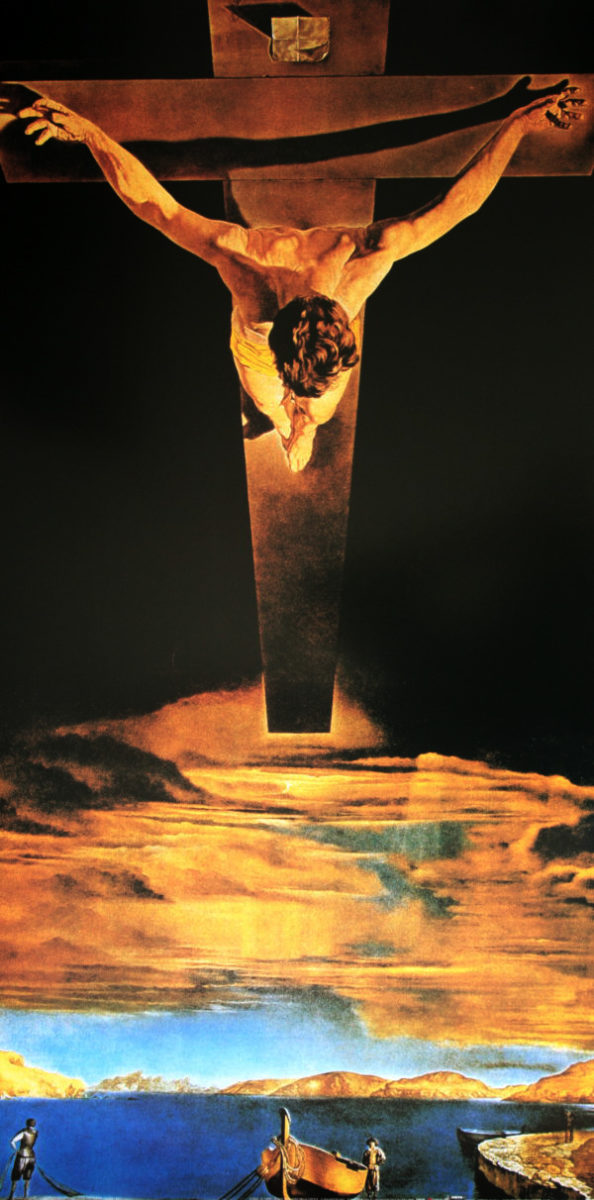

SALVADOR DALI SAID HE WAS inspired by a “cosmic” dream in which Christ was the nucleus of an atom when he painted his controversial depiction, Christ of St John of the Cross. This Christ has no crown of thorns, there is no blood, no puncture marks, no straining sinews, and he is poised above a body of water modeled on the Catalan coast. Indeed, we aren’t to know if this Christ is crucified or king of the world.

Dali seems to have tried to have it both ways: Christ’s body is still suspended on the cross, yet it’s a balletic pose, part of a longer choreography of which we are only witnessing one moment; he appears poised and the rest of the story subject to revision.

Taking the cue from Dali, if Jesus the human is the microcosm, and Christ the macrocosm, then the incarnation puts the divine right at the minutiae of human life; right at the center of the atom holding together the dualistic tensions of the world.

In this sense, the Cosmic Christ is our origin and destiny, but too vast in its transcendence to be grasped or made an object for our clinging. The incarnation—our incarnation—is inextricably tied to that larger universe, one reflecting the other; one needing the other. At the surface, that’s a radical statement: where would heaven be without us?

If God is hidden in plain sight, at the center of the atomistic structure of the physical world, we are free to discover our divinity not through ascent, but through rooting down in the here and now.

This puts a new spin on ‘ascension’, itself a problematic world. We are not taking flight from this world. Quite the opposite.

The wind is howling at our door

In the old Christological dualism, there is our fallen world and an imaginal redeemed world, the latter promised but ever-distant. It required faith and vigilance in the face of temptation to keep the redeemed world within cosmic sight, while generation after generation realized that it would never happen in their lifetimes.

On one level, this spoke to living as a testament to truth and embodying the world to come in the present moment; as if it was already here. Meanwhile, the wind howled at the door.

What’s changed? Has the time finally come? To answer that question, I return to—in a manner of speaking—God’s need of us, God’s desire of us, God’s unquenched hunger and thirst for us; the divine will and eagerness to love, over and over, and never enough.

Think of that: a love so grand, so vast, so uncontrollable, that it groans and swoons under its own inexpressible weight. This weight is, yet, weightless; a desire not a clinging; an eros consummated in the bridal chamber of the human heart—and then over again, not because it’s never enough like an addiction, but because there is no never and there is no enough.

Love’s bitter harvest

In human romance, we often crave for those early times of infatuation—when our lover reflects back to us our lovability. After a bitter season in which those passions barely seem to be still kindled, we may realize that we had treated the other as an object; their mirror an instrument—a self-object—to confirm our own worthiness.

Does love survive that fallow season of accounting? Like a slow bloom, another realization follows: it was always love and even our clinging was part of love’s mystery, unraveling the lesser love that made an idol of desire. Love makes masters of us all eventually.

Why would the divine lover make itself so inaccessible and remote, other than to ensure we don’t reduce it to the shape of our own limitations and even our own lean imaginings?

God at home

The microcosm, the active agent of reconciliation, is in the very marrow of our bones. God is in the detail, the minutiae, of this ‘fallen’ world. Has the wind at our doors ever blown so hard as now? There is only one answer: to be here more, not less.

The central movement of the work of John of the Cross, the Spanish mystic and poet whose sketch of Christ inspired Dali, is the release of God as object—which we can define and grasp at—to allow for God as subject.

As John wrote: “El centro del alma es Dios.” The centre of the soul is God.

Dali’s Christ is in a familiar position, suspended upon the cross-purposes of duality. Yet he is beyond torture and even crucifixion. He is beyond duality. What a potent image for where we find ourselves. The pose is familiar, but we are not bent into shape. We are free and the world changed but are yet to be convinced.

Dali painted Christ above his own Catalan coast. The Jesus story is endlessly adaptable to the contours of our life, so that in the end we see our own face reflected.

God-as-us and we-as-God

God as subject tears down every wall between our defended hearts and the inner swelling of life that knows no death, even while riding out every one of death’s stormy transitions.

All suffering in the end can be traduced to this: the captivity of love. The divine needs us as much as we need the divine. If we are one and the same as the love “that moves the sun and other stars”, then giving and receiving are measureless. Love only knows freedom.

The task is to remove the fetters; to allow God-as-us and we-as-God freedom of movement, to love radically, ceaselessly, hopelessly in the times beyond all reasonable hope. This is our rebirth, not a moment too soon or too late, because there is no never and there is no enough.